Space Tech

‘Tatooine-like’ exoplanet spotted by ground-based telescope

Star Wars came to Earth with the discovery of a rare exoplanet which orbits two stars at once, a concept introduced to many of us via Luke Skywalker’s home planet

A rare exoplanet which orbits around two stars at once – like Luke Skywalker’s home planet of Tatooine, in the Star Wars universe – has been detected using a ground-based telescope by a team led by the University of Birmingham at an observatory in France.

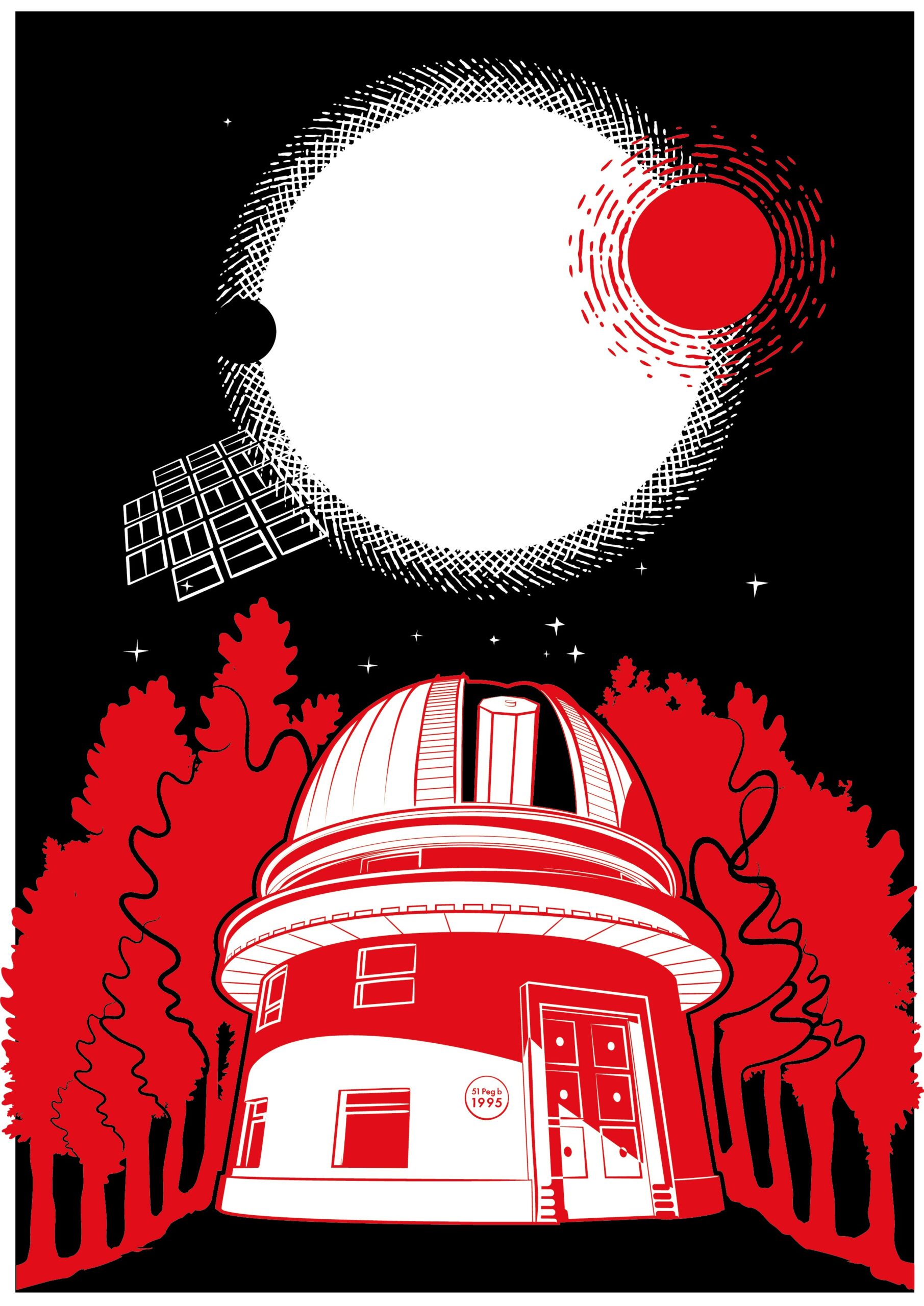

The planet, called Kepler-16b, had until now only been seen using the Kepler space telescope. It orbits around two stars, with the two orbits also orbiting one another, forming a binary star system. Kepler-16b is located 245 light-years from Earth and, like Tatooine, it would have two sunsets if you could stand on its surface.

The 193cm telescope used in the new observation is based at the Observatoire de Haute-Provence, in France. The team was able to detect the planet using the radial velocity method, in which astronomers observe a change in the velocity of a star as a planet orbits about it.

The detection of Kepler-16b using the radial velocity method is an important demonstration that it is possible to detect circumbinary planets using more traditional methods, at greater efficiency and lower cost than by using spacecrafts.

The radial velocity method is also more sensitive to additional planets in a system, and it can also measure the mass of a planet – its most fundamental property.

Having demonstrated the method using Kepler-16b, the team plans to continue the search for previously unknown circumbinary planets and help answer questions about how planets are formed. Usually, planets formation is thought to take place within a protoplanetary disc – a mass of dust and gas which surrounds a young star. However, this process may not be possible within a circumbinary system.

“Using this standard explanation, it is difficult to understand how circumbinary planets can exist,” says team leader Professor Amaury Triaud of the University of Birmingham. “That’s because the presence of two stars interferes with the protoplanetary disc, and this prevents dust from agglomerating into planets, a process called accretion.

“The planet may have formed far from the two stars, where their influence is weaker, and then moved inwards in a process called disc-driven migration. Alternatively, we may need to revise our understanding of the process of planetary accretion.”

Ohio State University’s Dr David Martino, who contributed to the discovery, says: “Circumbinary planets provide one of the clearest clues that disc-driven migration is a viable process, and that it happens regularly.”

A collaborator on the research, Dr Alexandre Santerne of the University of Marseille, says: “Kepler-16b was first discovered 10 years ago by NASA’s Kepler satellite using the transit method. This system was the most unexpected discovery made by Kepler. We chose to turn our telescope and recover Kepler-16 to demonstrate the validity of our radial-velocity methods.”

Dr Isabelle Boisse of the University of Marseille is the scientist in charge of the SOPHIE instrument that was used to collect the data. She says: “Our discovery shows how ground-based telescopes remain entirely relevant to modern exoplanet research and can be used for exciting new projects. Having shown we can detect Kepler-16b, we will now analyse data taken on many other binary star systems, and search for new circumbinary planets.”