Featured

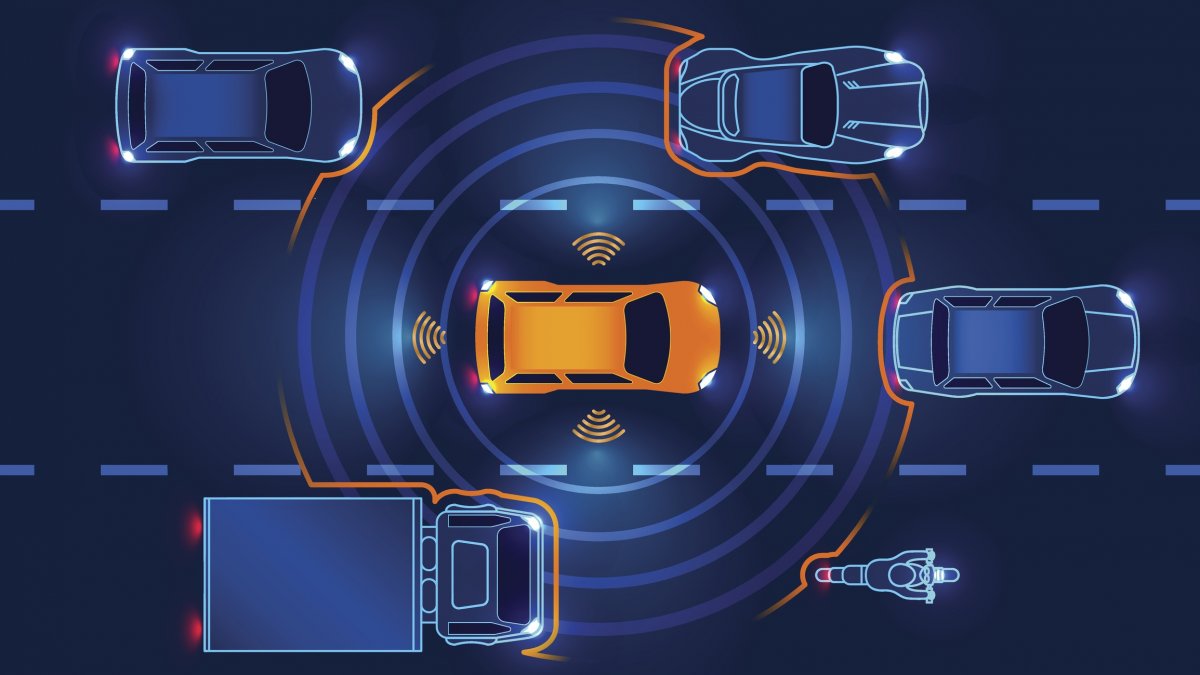

Autonomous driving a decade away

Despite substantial recent progress, fully automated driving systems that have no safety driver onboard will take at least a decade to deploy over large areas, with gradual expansion likely to happen region-by-region in specific categories of transportation.

This is a key conclusion of a new research brief examining the future of autonomous vehicles, released by the MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future. The brief is part of a series of subject-specific research projects by MIT faculty that will help frame America’s national discussion and policies about work, technology, and how to create greater shared prosperity.

Building on the Task Force’s interim 2019 report, “Work of the Future: Shaping Technologies and Institutions,” MIT Task Force members are providing analysis on topics including manufacturing, health care, tax reform, skills/training, and emerging technologies such as collaborative robotics and additive manufacturing. As the Task Force continues its research, the briefs will respond to the rapidly changing environment brought on by Covid-19 and its societal and economic impacts, and will inform the Task Force’s final report in November 2020.

“Automated driving technologies have promised to disrupt urban mobility for a long time. Our research explores the impact of autonomous vehicles on jobs and offers policy recommendations that will ease transitions and integration,” says David Mindell, co-chair of the MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future, Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Dibner Professor of the History of Engineering and Manufacturing at MIT, Founder/CEO of Humatics, and co-author of this report.

The brief, “Autonomous Vehicles, Mobility, and Employment Policy: The Roads Ahead,” co-authored by John Leonard, Task Force member and MIT Professor of Mechanical and Ocean Engineering and Erik Stayton, an MIT Doctoral Candidate in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology, and Society. The research brief draws on the authors’ research and experience in the engineering, social, and policy dimensions of automation and autonomy in extreme environments of the deep ocean and aerospace, as well as years of engagement with the auto industry, transit, and automated vehicle systems.

The briefconsiders the current state of automated driving technology and its potential impact on jobs. Despite substantial recent progress by the industry, fully automated driving systems that have no safety driver onboard will take at least a decade to deploy over large areas, even in regions with favorable weather and infrastructure; winter climates and rural areas will experience still longer transitions. Expansion will likely be gradual and will happen region-by-region in specific categories of transportation, resulting in wide variations in availability across the country.

Automated vehicles should be conceived as one element in a mobility mix, and as potential feeders for public transit rather than replacements for it, but unintended consequences such as increased congestion remain risks. The crucial role of public transit for connecting workers to workplaces will endure: the future of work depends in large part on how people get to work.

The automated vehicle transition will not be jobless. The longer rollout time for Level 4 autonomy provides time for sustained investments in workforce training that can help drivers and other mobility workers transition into new careers that support mobility systems and technologies. Transitioning from current-day driving jobs to these jobs represent potential pathways for employment, so long as job-training resources are available.

While many believe that increased automation will bring greater impacts to trucking than to passenger carrying vehicles, the impact on truck-driving jobs is not expected to be widespread in the short term. Truck drivers do more than just drive, and so human presence within even highly automated trucks would remain valuable for other reasons such as loading, unloading, and maintenance. Policy recommendations here include strengthening career pathways for drivers, increasing labor standards and worker protections, advancing public safety, creating good jobs via human-led truck platooning, and promoting safe and electric trucks.

Policymakers can act now to prepare for and minimize disruptions to the millions of jobs in ground transportation and related industries that may come in the future, while also fostering greater economic opportunity and mitigating environmental impacts by building safe and accessible mobility systems. AV operations will benefit from improvements to infrastructure. Investing in local and national infrastructure and forming public-private partnerships will greatly ease integration of automated systems into urban mobility systems.

“Human workers will remain essential to the operation of these systems for the foreseeable future, in roles that are both old and new,” says Leonard. “Ensuring a place for human workers in the automated mobility systems of the future is a key challenge for technologists and policy makers as we seek to improve mobility and safety, and thereby opportunity, for all.”

Share

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

| Thank you for Signing Up |