Featured

Now, beauty is in the AI of the beholder

Researchers have succeeded in making an AI understand our subjective notions of what makes faces attractive. The device demonstrated this knowledge by its ability to create new portraits on its own that were tailored to be found personally attractive to individuals. The results can be utilised, for example, in modelling preferences and decision-making as well as potentially identifying unconscious attitudes.

Researchers at the University of Helsinki and University of Copenhagen investigated whether a computer would be able to identify the facial features we consider attractive and, based on this, create new images matching our criteria. The researchers used artificial intelligence to interpret brain signals and combined the resulting brain-computer interface with a generative model of artificial faces. This enabled the computer to create facial images that appealed to individual preferences.

Senior researcher and docent Michiel Spapé from the Department of Psychology and Logopedics, University of Helsinki says: “In our previous studies, we designed models that could identify and control simple portrait features, such as hair colour and emotion. However, people largely agree on who is blonde and who smiles. Attractiveness is a more challenging subject of study, as it is associated with cultural and psychological factors that likely play unconscious roles in our individual preferences. Indeed, we often find it very hard to explain what it is exactly that makes something, or someone, beautiful: Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

The study, which combines computer science and psychology, was published in February in the IEEE Transactions in Affective Computing journal.

Preferences exposed by the brain

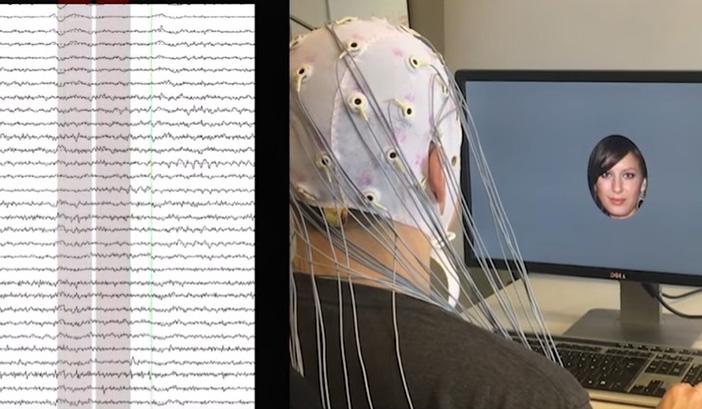

Initially, the researchers gave a generative adversarial neural network (GAN) the task of creating hundreds of artificial portraits. The images were shown, one at a time, to 30 volunteers who were asked to pay attention to faces they found attractive while their brain responses were recorded via electroencephalography (EEG).

Spapé says: “It worked a bit like the dating app Tinder: the participants ‘swiped right’ when coming across an attractive face. Here, however, they did not have to do anything but look at the images. We measured their immediate brain response to the images.”

The researchers analysed the EEG data with machine learning techniques, connecting individual EEG data through a brain-computer interface to a generative neural network.

“A brain-computer interface such as this is able to interpret users’ opinions on the attractiveness of a range of images,” says Academy Research Fellow and Associate Professor Tuukka Ruotsalo, who heads the project. “By interpreting their views, the AI model interpreting brain responses and the generative neural network modelling the face images can together produce an entirely new face image by combining what a particular person finds attractive.”

To test the validity of their modelling, the researchers generated new portraits for each participant, predicting they would find them personally attractive. Testing them in a double-blind procedure against matched controls, they found that the new images matched the preferences of the subjects with an accuracy of over 80%.

“The study demonstrates that we are capable of generating images that match personal preference by connecting an artificial neural network to brain responses,” says Spapé. “Succeeding in assessing attractiveness is especially significant, as this is such a poignant, psychological property of the stimuli. Computer vision has thus far been very successful at categorising images based on objective patterns. By bringing in brain responses to the mix, we show it is possible to detect and generate images based on psychological properties, like personal taste.”

Potential for exposing unconscious attitudes

Ultimately, the study may benefit society by advancing the capacity for computers to learn and increasingly understand subjective preferences, through interaction between AI solutions and brain-computer interfaces.

Spapé says: “If this is possible in something that is as personal and subjective as attractiveness, we may also be able to look into other cognitive functions such as perception and decision-making. Potentially, we might gear the device towards identifying stereotypes or implicit bias and better understand individual differences.”

Share

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

| Thank you for Signing Up |