EdTech

Nobel physics prize makes

business sense

The award of the biggest prize in science to two AI pioneers is cause for celebration and caution, writes ARTHUR GOLDSTUCK.

The Nobel prize for physics usually goes to someone who has come up with complex answer to even more complex questions. Often, the research being rewarded is so rarefied, few understand its significance at the time – or at any time.

This week was different.

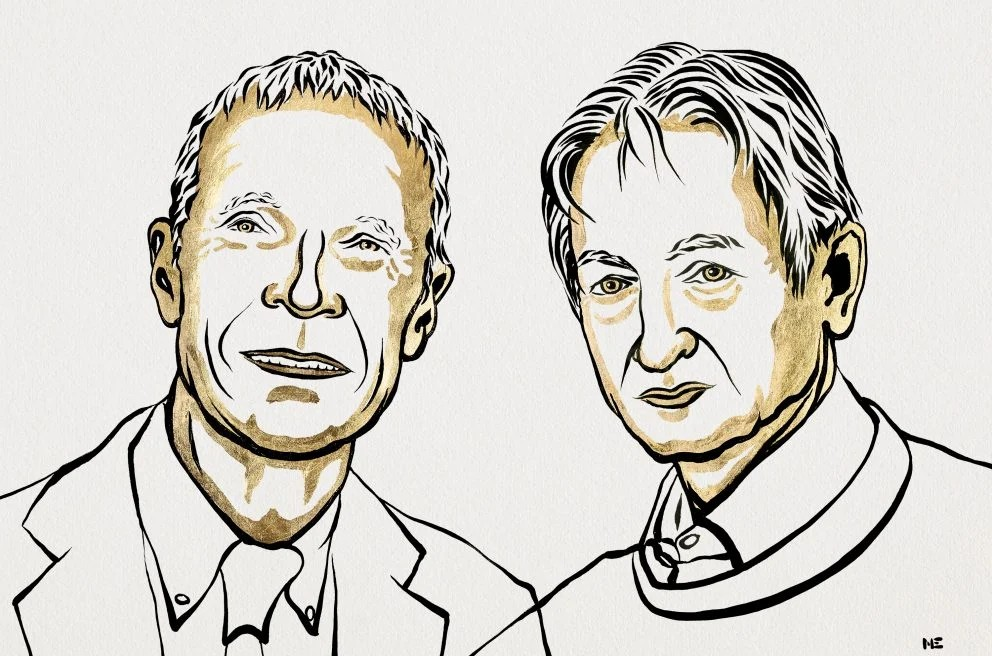

When the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics this week to John Hopfield and the legendary AI scientist Geoffrey Hinton for their pioneering work in artificial neural networks, it celebrated work that has become pivotal to a revolution sweeping the business world right now.

In simple terms, while they did not invent the field, as the Academy put it, they “used tools from physics to develop methods that are the foundation of today’s powerful machine learning”.

Hopfield’s work on associative memory and Hinton’s methods that autonomously find properties in data were not just academic triumphs. They made possible AI’s integration into industries such as finance, healthcare, and e-commerce, thanks to systems that can mimic human learning, recognise patterns, and perform tasks once thought impossible for machines.

That makes this year’s award unusually topical, and universally popular.

It is a testament to the power of researchers building on the work of those who have gone before: Hopfield invented a network that uses a method for saving and recreating patterns, called the Hopfield network; Hinton used the Hopfield network as the foundation for a new network that can learn to recognise patterns in data.

For business, the award highlights the extent to which complex research conducted decades ago can make the leap from purely academic exploration to real-world consequences.

The award is deeply appropriate for another reason: it has gone to two scientists who are leading voices of caution on the dangers of uncontrolled use of AI.

Hinton last year resigned his position as a vice president at Google so that he could “speak freely about the dangers of AI”.

While the business world’s rapid adoption of AI has led to staggering growth, with tools that optimise supply chains, predict market trends, and automate decision-making processes, it has also created an ethical minefield. Hinton has been outspoken about AI posing a greater existential threat than many other technologies combined, if it is not regulated. However, he admits that there is no “simple recipe”.

He told the Nobel website after being named prize winner: “With climate change, everybody knows what needs to be done. We need to stop burning carbon. It’s just a question of the political will to do that. And large companies making big profits not being willing to do that. But it’s clear what you need to do. Here we’re dealing with something where we have much less idea of what’s going to happen and what to do about it.”

He said that humanity was at a “bifurcation point in history” where it needed to figure out if there was even a way to deal with that threat.

“One thing governments can do is force the big companies to spend a lot more of their resources on safety research.”

Hopfield said in an address after the prize announcement: “As a physicist, I’m very unnerved by something which has no control, something which I don’t understand well enough so that I can understand what are the limits which one could drive that technology. That’s the question AI is pushing.”

These are not vague musings. The recognition of Hinton and Hopfield with the Nobel Prize serves as both a celebration and a caution. For companies rushing to develop or adopt AI, this year’s Nobel Prize should not only be seen as a nod to innovation, but also as a call to engage in discourse about risks and responsibilities.

* Arthur Goldstuck is CEO of World Wide Worx, editor-in-chief of Gadget.co.za and author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to AI. Follow him on social media on @art2gee.

- This article first appeared in The Sunday Times.